LEXINGTON — In mid-20th-century America, TV dads Ozzie Nelson, Ward Cleaver, and Desi Arnaz donned their wives’ aprons and mishaps and mayhem ensued.

Now some dads have taken over kitchen responsibilities, either out of necessity or because they love the inventive aspect of cooking. The bumbling dad has been replaced by some food-savvy home chefs, who enjoy their time at the stove with their kids as assistants.

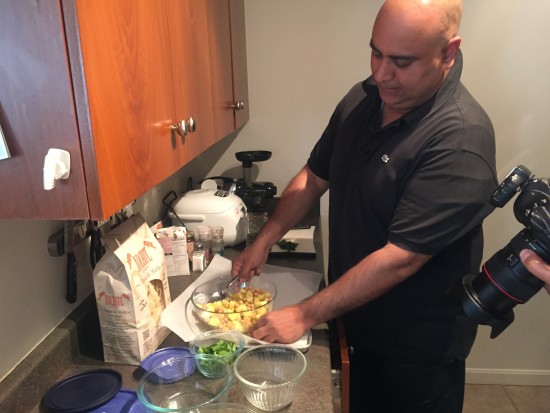

“I don’t actually call what I do cooking,” says Durjoy “Ace” Bhattacharjya. “I practice bricolage, putting a lot of disparate things together to create something new.” In his kitchen here, where he cooks for his wife, Usha Shanmugam, and their daughter, Sabrina, 5, the air is scented with roasting masala-dusted chickpeas and potatoes.

Bhattacharjya, 43, founder of a health care software company in Cambridge, is making chaat-style Indian nachos, a reflection of his childhood as a first-generation Indian-American; he grew up in Alabama and Massachusetts. Chaat are Indian street-food snacks that combine sweet, salty, tangy, and spicy flavors, he explains. One of his favorites is papri chaat (papri are wafers), made with layers of chickpeas and potatoes with coriander and tamarind chutneys, and chiles on the crunchy slices.

Last winter, when he was cooking for the Super Bowl, Bhattacharjya decided to substitute tortilla chips for the hard-to-find papri. He added salsa, Jack cheese, and a spritz of lime juice to complete his savory hybrid.

The melange of flavors and textures melded into an addictive combination of crunch, heat, and herbs. Sabrina helps wash the potatoes, and tear coriander and mint leaves for the garnish.

On Saturdays, “It’s weekend specials with Daddy,” Bhattacharjya says. His routine is to wake early, go for a coffee, and work for 2 hours. “Then I come home to make breakfast with Sabrina. We do pancakes together.”

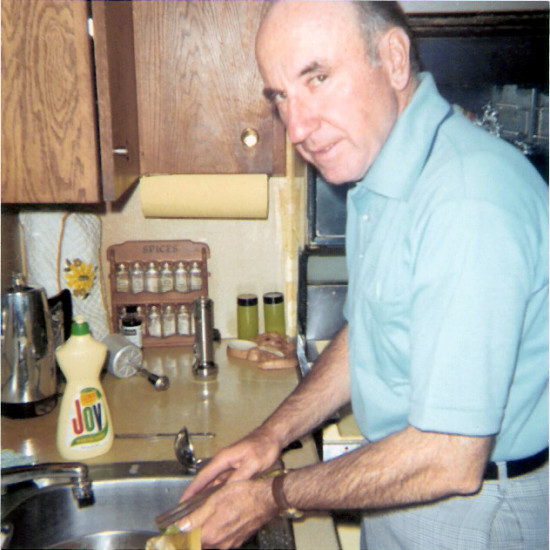

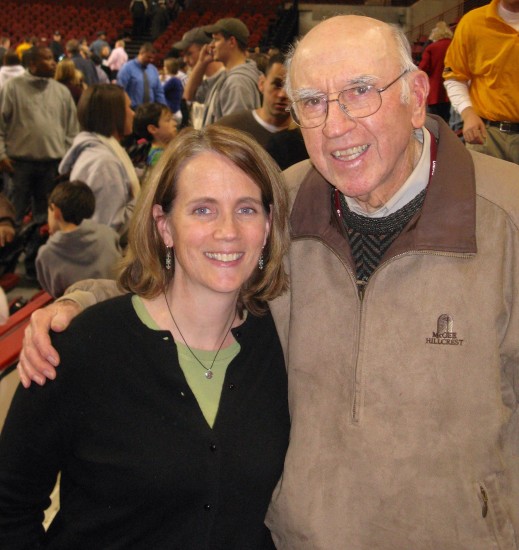

While Bhattacharjya is cooking for the sheer enjoyment, other dads cook because they have to. Katherine Bautze of Sudbury, who grew up in Agawam, was raised in a household where, after her mother died, her dad cooked every morning. Her father, William Walsh, now 95, made her and her seven siblings — all under 15 — breakfast every day.

Photos provided by Katherine Bautze

“My father and breakfast were building blocks in the foundation of my life,” writes Bautze in an e-mail. She recalls his military-style approach, never wavering from a fixed repertoire. Even today, she associates the days of the week with the assigned breakfasts: Mondays were cream of wheat, Tuesdays French toast, Wednesdays oatmeal, Thursdays eggs and bacon, Friday waffles, Saturdays cold cereal, Sundays eggs again. “The French toast was made with 2 eggs, 1 cup of milk and 8 slices of bread. The eggs were sunny-side up and fried in bacon,” writes Bautze, 54, who remembers the proportions and his methods all these years later.

When her father remarried and had another child, he continued to make an early hot meal for all the children. “After his breakfast shift ended, my father hung the red plaid robe on a hook, drove to work, and donned the robe of a district court judge in Springfield,” writes Bautze.

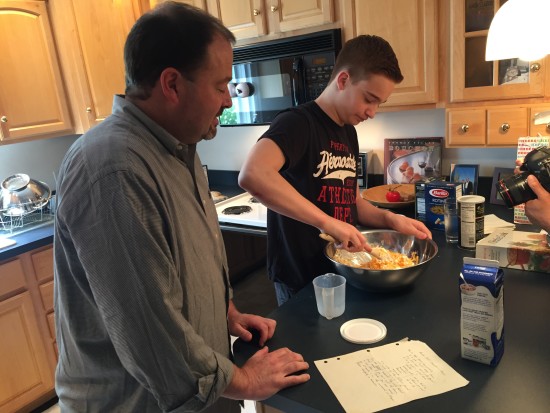

Theodore Gilman of Newton also recalls routines in his childhood kitchen in Longmeadow. His mother, Ellen Deborah Stern Gilman, a physician, “stormed in every night after work and made dinner for us four kids,” recalls Gilman. He enjoyed one-on-one time while grocery shopping with her weekly. He continues the activity with sons Ari, 19, a chemical engineering student in college, and Noah, 15, in his second year in the culinary arts program at Newton North High School.

Ted Gilman spent time with his mother grocery shopping every week and has two sons who like being in the kitchen. Noah Gilman assembles mac and cheese with breadcrumbs and cheddar.

When Gilman, 49, executive director of the Reischauer Institute of Japanese Studies at Harvard, was married, he and his former wife divided the household chores and he became chief cook. He knew little about the kitchen.

Today he shares culinary duties with his sons. One dish he and Noah make is Gilman’s grandmother’s macaroni and cheese. Ruth Stern’s recipe, written in his mother’s hand, sits on the counter. The teenager is comfortable in the kitchen, measuring, mixing, and cleaning as he goes. “If you don’t do that, it’s chaos,” he says.

For the mac and cheese, which seems to be a variation of a Jewish noodle pudding, Noah combines cottage cheese, sour cream, shredded cheddar, and milk in a bowl, adds partially cooked rotini, tips the mixture into a baking dish, and sprinkles the top with buttered breadcrumbs before baking.

The finished dish is hot with a golden crust, not especially difficult, and nourishing. Gilman began at the stove with minimal skills, his seasoning options “salt or no salt.” Noah’s grown up to be a cook and Ari a baker, says their proud father.

No adventures with Ozzie in this household.

Debra Samuels, bestselling author, food writer and cooking instructor,

Debra Samuels, bestselling author, food writer and cooking instructor,